On this page

Berkely the Christian is hunting me down. In the nicest possible way, of course. I suppose he thinks I need saving, which might well be true, but the difference between needing and wanting is important here. I am happy in my misery, I protest. Plus, I find his rather toothy smile unnerving. You can see the saliva.

'What do you mean exactly when you say 'There is always another point of view'?' he asked.

'Well,' I said. 'Suppose I am working very earnestly on a contract for some organisation or other, beavering away to achieve what we all agree is an important business goal. Suddenly, I might think what the hell am I doing this for? What does this project mean when measured against the Limitless Back-drop of Eternity? It's a complete waste of time.'

'So you give up?'

'Well, I might. But usually I'd think about how I would be letting people down if I stopped what I was doing and that they'd think badly of me if I did.'

'Your sense of duty wins through.'

'You could say that. The interesting thing, though, is that the situation involves three different points of view, each with its own set of values and that the values contradict each other or, at least, are incompatible. What's more, all those values are mine.'

'Some of them are more important than others,' he said.

'Why?'

'Because you don't walk out. You stay where you are and see it through.'

'But that doesn't mean the impulse to walk out is less important. If you judge your values on whether you apply them or not, there's not possibility of change. Plus, it might well be the case that the fact that I could walk out is the one thing that keeps me going.'

'But you won't walk out, will you?'

'Why not?'

'Because people would be disappointed.'

'What's wrong with disappointing people? If I always did what other people wanted I'd be no more than a slave to their desires.'

'How would you feel if they walked out on you?'

'I'd be disappointed, of course. But I'd get over it.'

'I think it depends on the size of the disappointment,' he said.

'Or on the strength of the impulse to get out of there.'

Berkely shook his head. He looked quite worried. 'How do you get any moral consistency?' he asked.

'100% consistency is impossible,' I said. 'People are more or less consistent. That's what makes them people.'

'God's consistent.'

'God's a machine, then.'

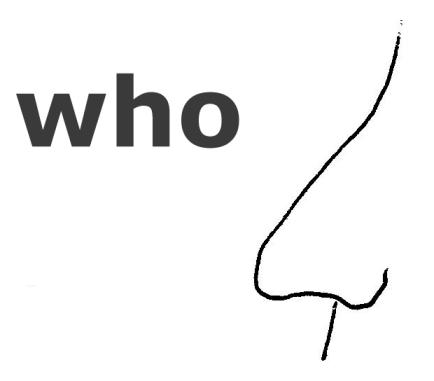

Amanda: And what's that supposed to be about?

Me: It's not supposed to be about anything. Except itself, maybe.

Amanda: The usual nonsense, in other words.

Me: It's an example of self-reference. Two questions, one of which answers the other.

Janice: Two questions? I don't get it.

Amanda: You don't need to get it. There's nothing to get.

Me: It's actually a statement about the meaning of life.

Amanda: It would be.

Me: A visual pun and...

Janice: A pun? Ah, now I get it. That's cute.

Woe is the man who becomes the centre of attention! Berkeley the Christian has been working his way through this blog and has come to the conclusion that I am in need of redemption. Ordinarily, I would be open to such a suggestion but when it comes from a government statistician who wears walk shorts and long socks and has an adam's apple like a date scone I feel an instinctive resistance. Unfairly, perhaps.

'It all seems very negative,' was how he began.

'What does?'

'All this talk about life being meaningless. It's sad to see someone in such psychological pain.'

'I'm not in pain,' I said. 'On the contrary, I feel quite liberated.'

'I used to feel that way. But I found that on the other side of liberation was Dark Despair.'

I had to admit he had a point so I said nothing.

He went on. 'And then I saw the light. Almost literally, you know? Like Paul on the road to Damascus. I suddenly realised that underpinning everything was this great power - the Love of God.'

'Well,' I said. 'I am not entirely against the idea that there's an underpinning. I'm not sure it's love, though. I doubt that whatever it is loves me or anyone else for that matter. Love seems an altogether too human an idea.'

'But most people believe in some ultimate coherence, don't they? They have a sense that there is an Above and Beyond that holds everything together.'

'Not Rupert,' I said.

'What about you?'

'Me?' I felt a little uncomfortable under Berkeley's beady gaze. 'You mean an ultimate principle?'

'Yes. Something like that.'

'Well, I have an ultimate principle,' I said.

'What is it?'

'That there is always another point of view.'

'Ah!' he said. 'Tolerance!'

'No. Not tolerance. At least, not just that. I mean there is always another point of view that I could adopt. Another way of looking at things. Another set of beliefs or values or attitudes that would make the situation seem quite different. I think it's called neuroticism.'

'You want to make a philosophy out of neuroticism?'

'Why not? You want to make one out of love.'

Ken finds Trevor very puzzling. I guess such an anarchic mind must pose something of a challenge to a life coach, whose professional assumptions are all based around progress towards a goal. Trevor, of course, isn't going anywhere and he seems to like it that way.

'He's never had a job?' Ken couldn't quite believe it.

'No, I don't think so. Although he did once run away to join a circus.'

'What happened?'

'They threw him out. He was upsetting the animals.'

'He doesn't seem exactly incapable.' Ken frowned. 'Is it a life-style choice?'

'Hard to say.'

'Hmm.'

What I perhaps should have said is that Trevor rarely gets past first base when it comes to jobs. He just can't cope with the normal protocols: filling in forms, for example. I've seen one of his attempts at an application. It went something like this.

First names: Adam and Eve

Last name: Beelzebub

Date of birth: I think my mother was going out with a musician at the time.

Sex: Not today, thank you.

Street address: Hi, there. Or Oy!

Postal address: Dear Trevor

Position sought: Horizontal.

Qualifications: I don't think I'd like to spend all day in bed. It's good to talk to people sometimes and they don't like coming into my room.

And so on. Does he do this deliberately? It's possible. But it is also possible that he's making honest responses.

Ken had better beware. I fear that trying to understand Trevor is the first step on the road to madness.

Kendall, it turns out, is not just a consultant psychologist. He is also a life coach. I am not quite sure what this involves unless it is helping rich people to get richer or to reconcile them to the terrible burden of their money. Given all this hobnobbing with the upper echelons, it is perhaps not surprising that Ken wears a pale blue tie and speaks in hushed tones of Captain Bland.

It was Trevor who brought up the subject of politics - on the assumption, I guess, that it was likely to be one of the more disruptive topics of conversation.

'When are you folk going to bring out your policies?' he asked.

'We don't need policies,' Ken said. 'We're doing fine without them. In fact the policies we have released haven't done us any good at all. Three statements and we're down three percentage points in the polls.'

'You're probably right,' I said. 'People don't seem to want a new direction. They want new faces.'

'And more in their pockets,' Rupert added.

Trevor nodded. 'That'd be good.'

'You're not going to get any more money,' I told him. 'You don't work.'

'I'm a public servant!' Trevor looked indignant.

'Oh, and what service do you offer?' Ken asked him.

'I allow the world to exercise its generosity. Without people like me, everyone would be going around feeling selfish and mean spirited.' He turned to Ken. 'I'm in the same business as you, really, aren't I? I'm an improver of people.'

There was a moment's silence. Ken did not look pleased. Fortunately, Janice changed the subject.

'I couldn't vote for National,' she said. 'Although I have to say John Key is kind of cute.'

'Cute?' Rupert gave a scornful snort.

'Yes. He's cuddly, you know? And he has that quirky little smile like he thinks it's funny but he's trying not to show it.'

'He's rich, too,' I said.

'That's all right. I don't mind that.'

'And he's right about one thing,' Trevor said. 'It is funny.'

'What is?' I asked.

'It. You know.'

'Which it is that?'

'The big one.'

'The Big It?'

'Yes.'

'That's funny?' Ken looked puzzled.

'Well, you couldn't take it seriously, could you?'

'I expect you take everything seriously,' I said to Ken.

'No,' he said. 'Not everything. I laughed the other day. I remember it distinctly.'

'Have you ever laughed at the sky?' Trevor asked.

'The sky's funny?'

'Oh, yes. Incredibly funny.' Trevor turned to me. 'don't you think so.'

'I know what you mean,' I said.

At last, Amanda has deigned to introduce us to her new man. He came round for a drink last evening. Tall, slim, chiseled features, sandy-blond hair, steady blue eyes. He is a triathlete and a highly successful consultant psychologist. His name is Kendall, Ken for short (Did I say anything?) and he makes me feel tired.

Ken is one of those people who have a very clear and intelligent view of how life should be conducted. He's the sort who, if you say to him in a moment of self-pitying exasperation 'Oh, God, what am I going to do?' will tell you. And he'll be right. At least, according to all measures of rational judgement he'll be right. He's very like Amanda in that respect. Indeed, apart from the fact that he votes National, it's not hard to see why they get on together.

Last night, for example, the conversation drifted round to this website and Ken asked me how many hits I got.

'I don't know,' I told him.

'There's software available that will tell you.'

'Yes, I've got some of that.'

'And...'

'I don't use it. It depresses me.'

'Why?'

'The numbers aren't that good.'

'How bad are they?'

'I don't know,' I said. 'I haven't looked.'

'The way to get your numbers up is to put yourself about a bit. You need to get other sites to mention yours. The great problem with the web is invisibility. You have to get yourself seen. Then, assuming your contents any good, word of mouth will take over.'

'Assuming,' I said.

'It just takes a bit of time.'

'Time is money,' I said.

'Ah, well. The only way to make money out of the web is advertising.'

'I don't like advertising.'

'How about product placement, then? What kind of soap do you use?'

I had to think for a moment. 'Cousins Imperial Leather.'

'There you are then.'

'So you think Johnson and Johnson, or whoever makes it, are going to pay me for mentioning Cousins Imperial Leather on my blog.'

'Why not? If it's popular enough?'

'Sounds like catch-22,' I said.

'Put the time in first and get the money later. It's called investment.'

As I said, he makes me feel tired. I think I'll go an make myself a nice cup of Dilmah and read The Dominion Post and wait for the cheques to arrive.

I am a bit annoyed. I've just got an email from Cynthia stating that she is 'disappointed by the navel gazing turn taken on [this] blog and has decided not to read it for a week or two'. Can she be serious? What have I done except say that one or two people like my book? Is that so terrible? If it were not for the fact that Cynthia makes up 14.29% of my regular audience, I would be tempted to a tart response. As it is, all I can rely on is wounded dignity. (What does 'navel-gazing' mean anyway? Watching the ships sail by?)

Let me just say that I've tried my very best to keep this whole thing on an even keel. Look at the restraint I've shown in not giving a broadside to the Montana judges! And I haven't mentioned the round minister for months, have I? Clearly, though, there is no mileage in trying to please everybody. Myself included. Between the Scylla of self-regard and the Charybdis of indiscretion, I am sunk

Henceforth, I shall write only in the spirit of Trevor. Random house rules. OK?

I forgot to mention that I was interviewed last week by that indefatigable worker for the arts, Lynn Freeman. I missed the broadcast because it was on Sunday afternoon and I was engaged at the time in a reading of a movie script my wife, Barbara, is working on it. Janice heard it, though. She said it was pretty good. Tune in if you're interested but take care its a seven minute podcast.

Janice asked me afterwards if Lynn was nervous.

'Why would she be nervous?'

'You know. That Montana thingy. I thought maybe she might be worried you were going to ask her awkward questions.'

Lynn, of course, is a member of that elite group of guardians of our taste, the Montana New Zealand Book Awards 2008 judging panel and I suppose Janice was referring to the fact that the judges have yet again ignored Felix's annual book of poems. Or perhaps it was their decision to shortlist only four works of fiction instead of the usual five.

Why Lynn would be worried, I am not sure, unless she was concerned that I might ask her something and reveal the answer on this blog where it might be picked up by one of the seven people who read it. If so, she need have no fear. My dear old white-haired mother taught me long ago never to ask awkward questions, at least not to anyone's face, and the last thing I want to do is to raise that Montana business again and have Felix go into one of his raves against the literary establishment.

No, what I would rather do is look to the future and mention the work of an unknown young writer. Her name is Sandra and she is writing a novel that is loosely based on that situation in Buller where the snails are getting in the way of the coal mine. It's called Black and its as much about the old mining communities of the West Coast as it is about the fight to save the snails. Sandra is also a minimalist poet and a graduate of Bill Manhire's creative writing course, of course, so we're expecting great things. I'll keep you posted.

I have just had a really encouraging email from Renee, who writes to say that she has just finished Gith and thoroughly enjoyed it. Un-put-down-able, she thought, although she used a more elegant form of expression. It is especially nice to get unsolicited compliments from fellow writers, people who know t the business.

The book also receives a mention on the blog of the wonderful Rachael King, who hasn't read it as yet but compliments the cover. (Well, that's a start.) She also admonishes me gently (at least I think it is an admonition) for Cynthia and Amanda's remarks with respect to navel gazing blogs. I sympathise but, wise as Rachael is, I fear she really doesn't understand the situation here. The idea that I or anyone else could tell Amanda what to say or not to say is, frankly, risible. Go ask the people who work with her at the Ministry of Rubber Bands, if you don't believe me. As for Cynthia, it all depends if she exists or not. If she does, then I fear she is likely to be as intractable as Amanda (although less forceful in her expression, no doubt). If she doesn't, then surely the remarks of a non-existent person mean nothing at all?

Now, I come to look again, Rachael does not actually mention Cynthia, although it was Cynthia who made the blog remarks. Amanda, of course, could well have made such remarks but she didn't. In this case. You see how easily things get misattributed?

Anyway, the point I want to make (before I get too confused and lose control of this sentence (and this post) altogether) is that Amanda has read Rachael's excellent novel The Sound of Butterflies and enjoyed it. I know she enjoyed it because a) she finished it and b) when I asked her what she thought of it she ignored me. Coming from someone who thinks that fiction consists of Jane Austen and bus tickets, this is high praise indeed.

Janice's friend Berkeley, who is a Senior Technician in the National Agency for Addition, Subtraction and Multiplication, came round for a visit yesterday. Berkeley is a Christian, one of the bright eyed and bushy tailed kind. He makes Rupert apoplectic and the rest of us, even Amanda, feel tired and jaded. I suppose if you're working at NAASM, you need something to keep you going. If it wasn't God, it would probably be hard drugs or sword dancing.

Trevor, of course, finds Berkeley irresistible. Trevor delights in faith of any kind, the stranger the better. Berkeley, for his part, does not realise that Trevor is an agent of Devil and always makes the mistake of taking him seriously. Yesterday, the subject was Intelligent Design.

'So,' Trevor said. '4004 BC. Is that right?'

'No, no. I think that's too literal,' Berkeley answered. 'I mean, I believe in science, evolution. You have to, don't you? Science is just God's way of doing things.'

'Maybe God decided to leave it all to chance,' Trevor said.

'It certainly feels like a botched experiment sometimes,' Amanda said.

'Laplace!' The burst from Rupert like steam from a ruptured boiler.

'What?' Berkeley stared at him.

'I think he's trying to say that science doesn't need the idea of God to explain anything,' I told him. 'Evolution is design without a purpose.'

'Evolution's ridiculous,' Trevor said. 'Who could possibly believe an idea like that?'

Berkeley looked confused for a moment. Was Trevor an ally or not? '

'When you look at the world... you know - the complexities of dna, quantum physics, things like that - there has to be a designer. Just the sheer impossibility of it working out exactly how it has. I mean, one little variation in the conditions and none of this would be possible.' Berkeley made a gesture towards the sunset. It silenced us all for a second or two.

Janice turned to me. 'What do you think?' she asked.

'Er...well.' I invariably feel awkward in such discussions. I always find myself changing sides. When Rupert is in full flight in God-delusion mode I want to argue against him. But then I feel the same with the likes of Berkeley.

'Intelligence and design seem like very human conceptions,' I said. 'Whatever God is, I don't think its human.'

'I think God created the world yesterday,' Trevor said. 'He just waved his magic wand and, ker-pow! It all came into being. Exactly the way it is'

Rupert laughed, enjoying what he supposed was Trevor's sarcasm. 'Maybe it was five minutes ago.'

'No. It was yesterday. It must have been. I remember feeling a bit funny just after breakfast. That's when it was. 8.14 am on the 10th of July 2008.'

As might be expected, Trevor's remark about life being pointless started one of those pointless discussions that typifies life on the veranda. I hesitate to try and paraphrase it except to say that there were twice as many points of view as people participating. The only lasting interest, as far as I can see, was whether or not this was an example of what I have come to hope might be an answer to life's demanding little questions - an argument the solution of which lies not in its content but in its form, an argument which shows us, in other words, rather than tells us.

Can I make sense of that? Probably not but I'll give it a go.

As Camus pointed out fifty or sixty years ago (at least, I think he did) the problem is not that life makes no sense but that it does not make complete sense. Any explanation, be it scientific, religious or every-day-commonsensical, breaks down somewhere and every explanation, sound though it might be in part, is contradicted by another equally sound or unsound explanation. Just like our arguments, all the points of view are valid to some degree but no two of them are fully compatible.

Janice, of course, would claim that everyone is right and all we have to do is be nice to one another. Amanda thinks that no one is right who doesn't take a sound practical view that avoids all abstraction and speculation. Rupert is equally adamant and in favour only of positions that can be reduced to clear logical statements, preferably ones that are expressed in a self-contained system of axioms and exhaustively defined formulae consisting of arcane symbols. Felix believes in nothing but passion, wine and poetry (not necessarily in that order). Trevor believes in chaos.

Maybe we have to acknowledge that art, in the broadest sense, is the only satisfactory answer. It is honest to the degree that it does not try to be anything other than it is; proud because it claims to matter for being no more than what it is; defiant in that it presents an instance of permanence in world in constant flux; and ultimately a failure because no one work of art can satisfy our restless hunger for meaning for more than a little while.

The epitome of human folly in other words.

Amanda's reaction to the new book was predictably forthright.

'Your usual thing, is it? Full of intellectual subtleties and self-referential ironies?'

'No,' I said. 'Not at all. Quite the opposite, in a way. It's a first person narrative and the main character's a bit thick. Well, he thinks he is, although he isn't really.'

'Sound typical.'

'I think it's really, really interesting,' Janice said.

Amanda turned on her. 'You don't know anything about it.'

'Yes I do.'

'You haven't read it.'

'I'm going to. And I've read the blurb.'

'Ah, well. If you believe the blurb, then you'll believe anything.'

'An unorthodox love story' Janice quoted. 'I like the sound of that.'

'Gay, is it?' Amanda asked.

'No,' I said.

'It's not sex with rabbits or inflatable dolls?'

'No.'

'Read it,' Janice told her.

'Hmm.' Amanda looked as if she were seriously considering the possibility for a moment. Then she said, 'I don't do fiction. Made up stories are pointless.'

'You like Jane Austen,' I said.'

'That's not fiction. It's great art.'

'Life's pretty pointless,' Trevor said. 'More pointless than fiction, anyway.

The new novel is out. Discreet bundles of copies have appeared on bookshop tables or propped face forward on shelves. It feels a bit strange. This is partly because there was no launch this time - Random House suggested we spend the money on publicity instead. Good idea, I thought at the time. Now? Well, I still think it's a good idea but there is less a sense of occasion than in the past.

Maybe the reason for that is not the marketing approach, though. Quite apart from all that I feel rather detached from this book. Well, not from the book itself but from the matter of its reception. There is much less of a feeling of anxiety about whether anyone will read it or much less buy it. Paradoxically, I am also being rather more assiduous about promoting the thing. I think that in the past I was really keen on the recognition, as if the attention paid to the book would somehow validate me personally. That meant that any impulse I felt towards promotion was also self-promotion; drawing attention to myself - a definite no-no in my cultural background. Now, when I don't feel so concerned about what other people think, I am more relaxed about drawing their attention to what I've done.

Speaking of which, it's called Gith and the cover looks like this.

I'm not entirely sure what to say about it. People who have read it say that it is very good. That might be true. If it is then it might also account, in part, for my general feeling of puzzlement. But then again, the shade of McGonagall looms as always.